RESEARCH AND CONTEMPORARY RECIPES

In considering the ingredients for recipe p010r (Jasper imitation):

Table of Contents

We have a clue in the first sentence: horn "as is used to make lanterns." This speaks to the thinness and translucency of the horn to be used in the recipe. I was able to find a 17th century recipe in Lémery's book, see below, to make horn for lanterns (or lanthorns, as they were called at the time) While this recipe gives direction in how to work the horn, it does not specify the type of horn either.

In secondary sources, ox or steer horn, being thinner, appeared to have been used to make lanthorns (http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/horn/hlant.html) Mark Carlson also gives advice on how to work horn. If thin, it is apparently easy to carve, and scrapings can be made using a knife.

NOTE: When looking for examples of horn lanterns, many have lost the sheets of horn, like the one in the picture from the Ashmolean museum in Oxford (Sheet iron, with a horn window originally, 34.5 cm high. AN1887.2)

To make horn for lanthorns recipe. Author: Lémery, Nicolas, 1645-1715.

Title: Modern curiosities of art & nature extracted out of the cabinets of the most eminent personages of the French court : together with the choicest secrets inmechanicks, communicated by the most approved artists of France / composed andexperimented by the Sieur Lemery, apothecary to the French king ; made English from the original French., London : Printed for Matthew Gilliflower ... and James Partridge..., 1685.

Copy from: Yale University Library, at EBBO

-While the recipe does not specify the actual colors to use, it does say which VARNISH to apply: turpentine or spike lavender varnish

-No specific COLORS are mentioned, only that they must be the opposite of opaque colors, that is, glazes (as seen with Marjolin, p065v): "opaque colours are not appropriate, no matter how fine they are."

Key in choosing colors is to think of the gemstones to imitate: jasper is found in a wide range of hues, cornelian is between orange and red. Since the recipe relates the horn scrapings with rose petals, I think it would be appropriate to paint with red, and we have already done some red pigments in the lab.

NOTE: The sentence "you know you can imitate roses with the scrapings of the said horn" starts the second paragraph, as a sort of transition between the two: The first paragraph only deals with the choice of horn to imitate jasper, while the second gives directions on how to varnish and apply the paint. Hence, it implies horn should be as thin as scrapings, but still we can experiment using both the horn sheet (flat) and the scrapings (curved), which will provide a sort of three- dimensional piece on which to imitate a gemstone.

Another entry to make roses our of horn scrapings or parchment is on the same page, with no further instructions though.

Check example: the Molded roses recipe and annotation done last year (p129r)

Main problem is that I have not found ANY recipe that uses horn as the basis for gemstone imitation!!! (not in ancient, contemporary or modern recipe books, and also asked librarian Meredith Levin, and she was not able to find anything either)

I can do some more research among Italian, Spanish or French books, but I did a preliminary search using the words cuerno, corno and corne respectively, with no success.

Even when looking for horn as furniture inlay, as suggested in the margin, I was not able to find any recipe.

Although I know engraved horn was not uncommon, and it was used in decorative objects around the 16th-17th centuries, it is proving difficult to find recipes/ examples in which horn is used as inlay. One example in the late 17th century is Boulle's marquetry, where tortoiseshell, ivory and horn were used, among other materials.

Check Boulle's article in the Conservation Information Network:

http://www.bcin.ca/Interface/openbcin.cgi?submit=submit&Chinkey=112945

Despite the French cabinet-maker is not contemporary to the manuscript, it is interesting to think about André Charles Boulle's pieces of furniture in relation to this recipe. Not only because he used horn inlays, but particularly because his furniture materials originally belonged to gold smithing (and the author of BnF 640 appears to know a lot about goldsmithing techniques, in the painting on glass recipe, he also refers to the basse-taille enamel technique): Boulle covered the furniture with gilded copper sheets, inlayed silver, engraved tin, used as a support for transferred fragments of mother-of-pearl, ivory, tortoise-shell, horn...

Still, the horn in this case is not used to counterfeit gemstones. It is thus possible that counterfeiting jasper or cornelian using horn is unusual anyways. I have been looking at a lot of gems in different materials, and I cannot think of a single piece of painted horn. On the other hand, at EBBO, I found old recipes to dye horn, indicating some decorative purpose.

Check: Adele Schaverien. Horn: its history and its uses. 2006 (only at Watson, or NYPL Schwarzman building)

If there is indeed no other recorded recipe of gem imitation using horn, how unique is the BnF Ms. Fr. 640?

The author seems to prefer it to glass, and coloring glass to imitate gemstones was very common, already since Roman times. Is the author being original here? We can assume that he observed the optical effects of the paint in both glass and horn, and prefers the second, "for its fatty polish similar to jasper." However, there is a slight contradiction in the recipe's main body and the subtitle that reads "thin glass looks very fine for his effect," right underneath the Jasper imitation's main title.

Main ingredients needed: horn, glaze colors, varnish, spike lavender oil

Experiments: glazes and varnishes. Applications on the horn (flat and curved), and on glass too, test the difference.

Recipe directions in order:

1. Imitate your cornelian underneath the thin horn

2. Before the colors, apply a clear base of varnish

3. Oil the unpainted underside with spike lavender oil

HORN IN JEWELRY

Horn appears to have been a common material in amulets, as a powerful material to protect from harm, or to attract good fortune. Sharp objects, such as teeth or horns, were believed to have the ability to protect against the evil eye.

The V&A has a beautiful example from the Renaissance (1550): a pendant in the shape of a ship, made of enameled gold and narwhal tusk (then thought to be unicorn, but in reality from the Arctic whale) Perhaps it is in this example that I can better imagine horn being used in lieu of gemstones during the Renaissance! More details

While ahistorical, in the 1900s Lalique (France) and Partridge (England) extensively used horn to make jewelry. See

1600-1700 EXAMPLES: HORN FITTINGS IN FURNITURE

-Larger than a casket, this wig cabinet on view at the Met has painted horn as a substitute for tortoiseshell! (Gallery 551)

Interestingly, the Met curator Wolfram Koeppe rejects the previous hypothesis that the maker, Johann Daniel Sommer, had done this piece in Augsburg, on the basis that in that town he could not have used painted horn as a substitute for tortoiseshell. Indeed, Augsburg guaranteed the quality of its luxury goods and ruled that "nobody should be deceived with oxhorn."

Maker: Johann Daniel Sommer II (German, 1643–1698?)

Date: ca. 1685

Culture: German, Künzelzau

Medium: Oak and walnut veneered with ebony, ebonized wood, and marquetry of pewter and mother-of-pearl on horn over paint, simulating tortoiseshell; silver; brocaded damask (not original)

Dimensions: 16 × 18 × 13 1/2 in. (40.6 × 45.7 × 34.3 cm)

Credit Line: Purchase, Rogers Fund and Cynthia Hazen Polsky Gift, 2004

Accession Number: 2004.417

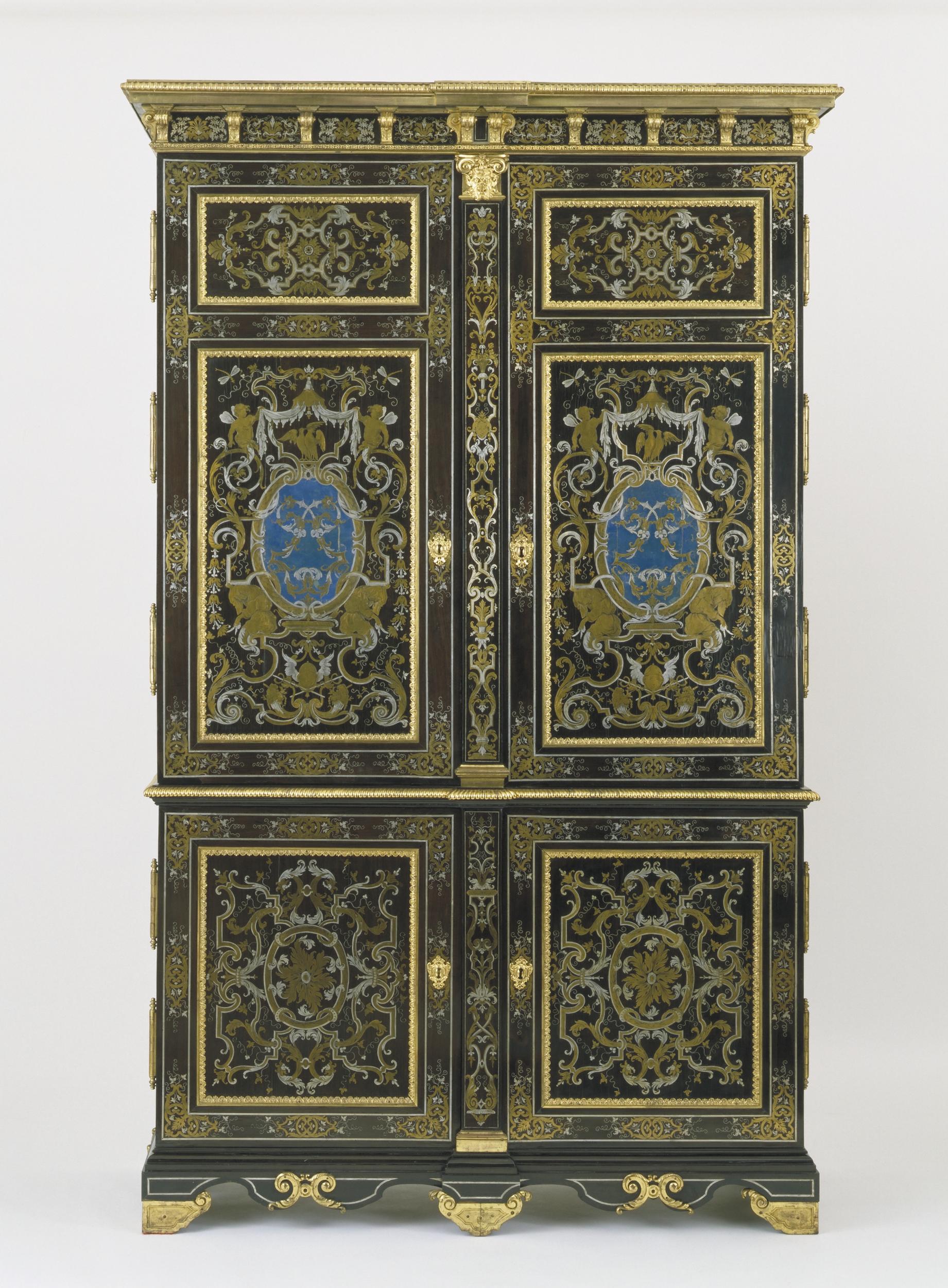

-Boulle's time, ca. 1700, but different cabinet maker: a large cupboard with marquetry of engraved pewter and brass, and panels of clear horn over turquoise pigment in the upper doors, at the V&A. More info

Ebony veneer, with marquetry of engraved pewter and brass and panels of clear horn over blue pigment, on an oak carcase

Other examples in the V&A collection are small caskets or also a superb portable writing desk, with the coat of arms of the Duke of Urbino ca. 1600), though the horn is said to be in small areas (not clarified). See here

Name: Donna, Wenrui and Ana

Date and Time:

2015.11.23, 11:40 am

Location: Lab 226 ChandlerSubject: Working horn

Working with the material translates into a total contact with it, all senses involved. We had to use safety glasses, given the amount of dust generated from cutting and polishing the horn, but we didn’t put gloves on, to have more control and held the horn in place. We could also smell the animal fat after a while cutting and filing. Horn is an organic material: the keratinous tissue that covers the bony core on the heads of certain bovine and ovine species.

Origin of our horn: 2 scales of honey horn, bought online through Ebay.

2 pieces Honey Horn Flat Blank Plate Scales 160x 60x5-6 mm (~6.3”x2.5”x.2”)

The seller had not specified the animal type, and I had checked that honey horn usually derived from bovine species, which I thought would be ox or cow. I contacted the seller, who only responded after the horn had been ordered. Even if the horn came from Virginia, it turned out to be water buffalo horn, from India. Initially, using buffalo horn was not the intention, since the recipe from a French manuscript more likely called for ox or cow horn. However, the color of water buffalo can be of a clear color too, like the honey horn we were sent, so it is actually close to ox horn. See comparison of horn plates online at: http://www.hornnatural.com/products.html

Cutting the horn

- We cut the horn in smaller pieces with a jeweler’s saw (recipe does not explain how to work the horn or which tools to use, but it tells you what the horn should look like: thin like glass, as used to make lanterns) Donna, who has years of experience making jewelry herself, taught us how to tense the saw to cut the horn.

- The cutting process required for us to concentrate, governing our hands to do two different actions at the same time: the left hand pressed the horn in place, while the right hand had to cut the horn with a dynamic movement up and down, without rushing or pressing to get to the other side (always a good reminder for me: to be patient is essential at the workshop!)

- Given that we are imitating gems, and we want the translucency of glass according to the recipe, we decided to cut the horn even thinner. While Donna cut the horn in half, to a thickness of 1 inch (originally 2 inches), Wenrui and I polished: she used a smaller file, which she moved around and top of the horn piece, making it thinner in the process. I used the larger file, positioned flat on the table. I made sure to file the edges too, that were rough to the touch after being cut with the saw. Also, in thinking of gems and furniture inlays, I decided to round the corners too.

Heating the horn for luster and to check the malleable qualities of the material.

- Around 1 pm, we tried burning two of the polished pieces of horn, only one of the sides, for luster and a glossy finished. Donna and Joel helped us set up a lamp with alcohol, to have a moderate flame. I took a picture before and after, and the horn on the side left over the flame for a minute was visibly more yellow and shiny.

- We also heated a larger piece of horn, to experiment with its malleable qualities: on the flame, we bent and straightened the horn several times. We ended up burning the middle part, which became brittle and broke. The recipe also compares horn to glass, and indeed the process of heating the horn reminded me of the process of melting glass to make it workable, and it became fragile as well. Horn is of course more resistant than glass, but the more it is worked, the more delicate it becomes too.

Indeed, experimenting with materials gives us the opportunity to understand their properties. Heating horn showed us that it is somewhat thermoplastic: when cold, it is hard, but when heated it is pretty workable. In the past, horn would have been used for many purposes where plastic would now be used. The problem is that, being organic, horn decomposes in the ground when discarded, so little physical evidence remains of the former extended use of horn.

Moreover, before working the horn, I would have never said it shares properties with glass, which is something the recipe makes explicit.

Varnish (p003r in manuscript; consisting of:

20 grams of larch turpentine Kremer - 62000

10 grams of turpentine (distilled oil of) Winsor and Newton. Mixed together and heated up, done by Marjolin and Jenny. We will also try making varnish ourselves)

- At 2 pm, Wenrui and I each took one of the polished pieces and applied varnish on the roughest side, with a brush. The horn instantly acquired a beautiful glossy finished, and I can now understand why the author practitioner says, “the horn gives a luster and a fatty polish similar to jasper.”

- The recipe’s next direction is to paint over the varnished side, which we will do next Monday, when varnish is dried.

Name: Emilie, Wenrui and Ana

Date and Time:

2015.11.30, 10:40 am

Location: Lab 226 ChandlerSubject: Varnish and Pigment experiments on the horn

Horn recipe gives two options to apply with the colors: either turpentine or aspic varnish. Safety protocol doc here

See experiment: Turpentine Varnish

-We did the Turpentine varnish first, heating Venice turpentine and distilled turpentine oil according to recipe p003r_a2, Varnish for paintings

-Then, we also did Aspic oil varnish, lavender spike oil and sandarac: <id>p004r_1</id>

Interesting to note that the author gives further details on the use of the lavender spike oil varnish (and there are some national references to my country Spain: when I lived and studied in the south of Spain, Granada, there were still guitar maker workshops opened!): "To avoid the trouble of polishing their <m>ebony</m>, <pro>framemakers</pro> varnish it with this. So do <pro>guitarmakers</pro>. This [varnish] is not as fitting for paintings as fine <m>turpentine varnish</m>, though it is good for the paintings’ moldings. When <m>linseed varnish</m> was in use, one would not commonly varnish the landscape of a painting because it would turn the landscape yellow. But with <m>turpentine varnish</m> one varnishes everywhere. Instead of <m>sandarac</m>, you can add to it pulverized <m>mastic</m> drop by drop or otherwise, and it will dry more quickly.</ab>

A couple of frustrations and learning from mistakes:

At first, in the directions given by the author practitioner it was ambiguous if the turpentine was used as varnish or oil.

More importantly, before doing the experiment, we thought the varnish was applied separately to the paints, but then in the reconstruction, it became very clear that the author applies varnish with the colors.

-On turpentine: we checked the language of the original recipe and folio again. While in the horn recipe, the author does not use the word varnish after turpentine, as he does with Aspic, there are other instances in the manuscript in which he refers to "turpentine" alone as the thicker Venice turpentine to be combined with distilled turpentine in order to make a varnish for the paint. In the above recipe for varnish on paint using turpentine (p003r_a2), one reads:

"But if you find it too thick, add more oil, whereas if it is too clear, you can thicken it by putting a little turpentine."

Thus, the author practitioner does use the word oil when he wants to be specific about using turpentine oil, but when he uses the word turpentine only, it refers to the thicker Venice kind.

Further evidence is found in a note to the varnish recipes:

<note id=”p003r_c2a>You need a little more turpentine than turpentine oil to thicken the varnish, which you need to apply with your finger in order to spread it thinner and less thick because when it is thick, it turns yellow and gathers [together]. Varnish is not used to make paintings shine, because it just takes the light out of them.</note>

(Side note: About applying it with the finger, I can see the brushstrokes in the horn, so I understand the author is concerned about applying it more uniformly. But to the touch, varnish is so sticky, and also tough on the skin, it can cause blistering! Hands are the most important tools for the craftsman! I can imagine he might have toughened his hands’ skin after years of workshop practice, but still it must take courage to do this, especially when knowing so well the properties of materials)

-About colors: Today varnish is considered mostly a paint protection, and so applied separately, especially on wood and furniture. However, when I tried to apply the colors in the horn pieces we coated with the turpentine varnish last week, the varnish protected the horn and acted as a repellent.

This was very logical and apparent when trying to paint the colors over, but it was not clear when reading the recipe, whether in the original French or translated English:

"Couleurs pour ce <m>jaspe</m> veulent avoyr fonds avecq<lb/>la <m>tourmentine claire</m> ou <m>vernis daspic</m>"

"The colors for this <m>jasper</m>need to have as a base clear <m>turpentine</m>or <m>spike lavender varnish</m>."

When mixing the pigment with the varnish, the color not only binds better together, it also binds to the horn, and giving the same glossy finished we had seen with the varnish alone last week.

Because today we buy the varnish with a previously added tone, darker or lighter, it was new for me to think of varnish as an oil that can be mixed with the colors previously, thickening them and giving them luster. But this is in any painting manual (too bad I learned acrylic and not oil painting, I would have known this!!!) Similarly, it was a disaster to mix the colors with just turpentine, as it thins the colors.

Knowing all this, after 3 pm:

I used madder lake powder to do red, blending walnut oil before mixing the aspic varnish.

After the manuscript's recipe to do glazes (since the horn recipe says to use the opposite to opaque colors): 6r, which we looked at with Marjolin Bol for gilding, has a last paragraph on glazing pigments:

Before the application on horn, I painted two squares on my panel as tests: one square with red madder lake+ aspic oil, another square with the addition of walnut oil.

Trying both ways on the horn too, with and without the oil, helped me see a more brilliant color in the horn with extra walnut oil. This is interesting, since the author also tells us to put lavender oil on the unpainted side. Reminded me what we talked with Marjolin about the enhancement of gemstones. It sounds like the author wants to enhance the translucency of the horn.

CAUTION: the varnish dries pretty fast, so have only a small quantity to mix with your color, and work as fast as you can to blend all together and apply. Adding some water at stages works with the color, but you need to add the right quantity of varnish so that the final effect is shiny.

Name: Ana with Joseph Godla, Chief Conservator at the Frick

Date and Time:

2015.12.15, 11 am- 12.45 pm

Location: Frick conservation labSubject: Thinning the horn

- As a former cabinetmaker, Godla had the necessary tools to this the horn. He first tried with different sharpened blades, without success, realizing how much

harder horn was in comparison to wood. He finally decided to use a plane for wood.

- After sharpening the edge several times, it took over an hour to get the horn to the thinness of a leaf, as it will be appropriate for lanterns according to the author-practitioner.

- The thinning generated a lot of scrapings. I saved a full bag of this waste for the rose imitation, which is in the same recipe 10r.

Name: Ana and Donna Bilak

Date and Time:

2015.12.21, 12 pm- 04.30 pm

Location: Lab 226 ChandlerSubject: Rose and Jasper imitation using horn

1. Making rose with the horn scrapings. 12- 2 pm

Since I was mixing turpentine varnish with the pigments, I wore gloves and did the experiment in the fume hood.

- First, I tried arranging the unpainted scrapings to create the rose. The material is naturally curled and the curls easily fold into one another, so I notice that when arranged concentrically, the horn scrapings do look like rose petals!

- Second, I made the pigment according to the recipe 6r for glazes. The madder lake was a deep red color but created more particles than the Venice red, which was much smoother. I did a layer with one color, and the Venice red top.

- It was easy to apply the paint with a brush, which make me think about the author-practitioner’s alternative to make the rose using parchment instead of horn scrapings. The sensation was equivalent to painting white pieces of thick paper, only that the curls made it a little bit more challenging than a flat surface.

- The varnish and walnut oil mixed with the pigments created a bright, glossy and luster finish

- After a couple of hours, leaving it to dry, I composed the rose with the painted horn curls. The difference I notice from the unpainted horn is that the scrapings, while still curled, were more malleable now.

2. Painting the thin horn as red and green/blue jasper (Corsica variety of jasper), 2.30-4.30 pm

- With Donna, we cut the thin sheet of horn in 4 pieces, two square and two rectangular, thinking of the gems decorating pietre dure tables. Given that jasper is found in a variety of colors, I painted the square pieces in Venice red, and the rectangulars using verdigris.

- Getting the pigment mixed with oil and varnish to the right consistency is a challenge, since the recipe does not give any proportions. The first trial was too opaque, which is what the author-practitioner specifies to avoid. By adding more oil, the paint thins out and it is also possible to recreate the various shades of a gemstone, with more translucency

- With the verdigris, I was careful not to use the aspic varnish, but the turpentine varnish, as the manuscript directs (in glazes recipe 6r) Apparently aspic varnish is not suitable for verdigris. This comment is very interesting, as it reminds us that the author-practitioner also went through a series of trials and errors.

- The painted horn looked very much like colored glass. In fact, with Wenrui we did the same kind of paint for the reverse painting on glass recipe (check her field notes and annotation for recipe 39v), with the exception of the mastic added to make the color adhere to the glass. The comparison to colored glass is not surprising, since the recipe 10r introduces horn as a better alternative to thin glass. Moreover, colored glass has been used in gemstone imitation since antiquity.

- In the reconstruction, the main observable difference between painted glass and horn is when looking at the paint through the unpainted side. Through glass the color is bright, while through horn, the color is attenuated, it does not look shiny. Opaque colors do not work on horn though, because they do not let light through, which enriches the nuances of the painted material and keeps the translucency of thin horn

- When I left around 4.30 pm, the paint was not dried, so I could not apply the spike lavender oil to the unpainted side, as I had done on November 11 with the thicker pieces of horn. Then, I already notice that the resulting horn loses striations, which again makes it more translucent and helps admire the painted color on the other side.

ASPECTS TO KEEP IN MIND WHEN MAKING FIELD NOTES

- note time

- note (changing) conditions in the room

- note temperature of ingredients to be processed (e.g. cold from fridge, room temperature etc.)

- document materials, equipment, and processes in writing and with photographs

- notes on ingredients and equipment (where did you get them? issues of authenticity)

- note precisely the scales and temperatures you used (please indicate how you interpreted imprecise recipe instruction)

- see also our informal template for recipe reconstructions